|

Can you explain exactly the situation at stake and the historical development of it?

The state of Saxony has a conservative government which has been constantly cutting university budgets since 1993. Today the teaching personnel of Leipzig University is half as big as it was in 1993, whereas the number of students has doubled and is still growing (2004: 30,000).The results are felt by most students: new reading materials and foreign reading materials are largely unavailable at the university library. Seminars are overcrowded or access is determined by lottery. Sometimes there are even not enough teachers to hold final exams.

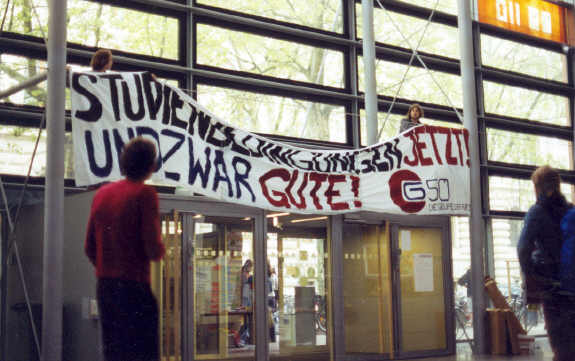

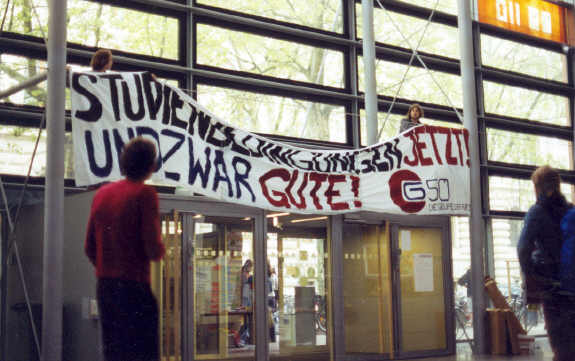

Who are you? And What are you fighting for (or against)? We are about 50 students from all departments of Leipzig University fighting for better studying conditions at universities in Saxony.

How are you fighting for it?

Student protest is often only symbolic. They occur on a regular basis every three to five years. Protests often show and symbolize discontent with the situation at universities, and although they may intend to change policy, they are not linked to the political sphere at all. They don’t take into account the political game that produces higher education policy. Consequently, the protests are misplaced and they are badly timed. First, protests are often misplaced because they do not provoke a discussion about higher education in the political system. This is due to the large distance between protests and the political sphere. Activists should contact political actors in a direct and more aggressive way. Second, they are often badly timed, as protests should happen when the political systems is less stable than usual; for example, in close connection to elections, when political actors are more open to the wishes of their constituencies. We have decided to be more pragmatic and have begun entering the political sphere. Our political analysis is as follows: the conservative government of Saxony will lose absolute majority in the regional elections in September 2004. Therefore, the now-governing CDU [Christian Democratic Union] will need a partner to form a coalition government. This will be the SPD [Social Democrat Party]. This is based on three reasons:

- I am optimistic about the strength of democracy! People should not accept an absolute majority in the Saxony parliament anymore.

- The former Minsterpräsident of Saxony Biedenkopf (called König Kurt (King Kurt)) had to leave his post to the former Minister of Finance, Georg Milbradt, who is not half as charismatic and therefore much less popular.

- The Greens might enter the Saxon Parliament, thereby increasing the votes that have to be won in order to keep an absolute majority in Parliament.

We therefore decided to lobby the CDU’s opposition, especially the SPD. That is, we offer help for their election campaign, they integrate our political program into their main political documents.

How is this group organized?

We have formed three expert teams:

-The policy team formulating our policy goals

- The communications team building up relations with press agencies, local newspapers, etc. and creating events to bring our point to the public

- The lobbying team – which has been analyzing the situation of our strategic partner - constantly contacting decision-makers in order to present our goals and our capacity to change the political landscape of Saxony.

But Leipzig University does need more money, doesn't it? Given that the eastern German economy is weak, how do you propose the university raise money?

I would argue differently: the economy is weak because universities here are not as strong as in other regions of the world, where universities form the centers of the regional innovation systems. Increasing innovation by supporting strong universities and good education conditions would be the solution for German states to promote their economic well-being. On the other hand, universities do not adequately fulfil their role as catalyst for the regional system of innovation. Universities are often not adequately linked to their regional background.

|

|

|

It’s my understanding that the way that most German students go to college is that their parents pay for their housing and living, and a small semester fee (50 euro), or, if parents aren’t wealthy enough, students get a stipend from the government to live and study that is paid back after graduation. Is this accurate? What is at stake of being changed?

The problem with the government stipend has been that only a few students actually get it – since funds have been very limited. Therefore, many students have to work while they study. As we are facing very high unemployment in east Germany [an average of about 20%], students jobs are quite rare and they are not very well paid. Furthermore, many students have problems getting into seminars if they don’t make the lottery, and then they might not be able prove that they are trying to study, which leads to being cut off the government stipend.

Where does investment for the university come from aside from the government. Alumni? Business? Private Organizations? Do you think these other sources are viable options (as in that they could potentially invest)? Or, philosophically, or fundamentally, do you think the government, as a reflection of the society, and concerned with the society, should maintain responsibility for higher education?

Most universities (there is only one private university in Witten-Herdecke – which is heavily subsidized by the state and some of the largest German corporations) are financed by the Länder, the regional governments. Higher Education does fall under the authority of the Länder. There does exist, as well, federal legislation to govern the framework of higher education. In 1998, the Social Democratic-Green government introduced a rule into this legislation which bans the introduction of tuition fees by regional governments and parliaments. University education is seen as a meritorious good, meaning that it is a good not produced in the societally appropriate quantity. Therefore, the state has to intervene to lower the cost of the good in order to increase its supply. This good, however, has a lot of positive external effects. Those effects would not occur if fewer people studied. Consequently, the costs for the public university system are lower than the benefits from positive external effects.

How do you calculate cost and benefits?

As with all external effects a full accounting of costs and benefits is not possible. However I would hold the benefits of a highly educated society to be invaluable to every member of that society.

The United States' university system is in many ways fundamentally different: there’s a high tuition cost (between $3,000 – 40,000 per year), a high level of private investment (for example from food distributors who want monopoly on what is sold in the cafeterias, or, more integrally, science corporations looking for specific research work). As a result, universities are wealthy, and even comparisons of state schools (Rutgers where I went, and Leipzig University, where I am typing) show the distinction. Wealthy universities mean a lot of nice things for the students: well-stocked libraries, funding for student activities, a higher density of professors. It also requires compromise. Where and how do you think the balance should be drawn?

Of course universities should have enough money – that is not the question. But the money should come from the state and not from the individual student.

Where (or how) should the balance be drawn between offering education to everyone, and making restrictions in order to insure that that education is valuable?

Education does incorporate an economic and social value and it is multiplied by the network effect of education. Education is more valuable if everyone is educated! Costs (time spent on explaining complicated processes, asking for the way to the next tram station in a foreign language, etc.) for communication is dramatically diminished, conflicts in society can be solved more intelligently – the society is more democratic as educated people are more likely to take part in political processes, inventions and innovation occur more often – economic growth is augmented.

Can capitalism (or privatization) help? What is then lost?

Capitalism is not democracy. If some people can buy certificates (and this is certainly the case in privatized and capitalist education systems) elites can reproduce themselves more easily. |